Example standard operating procedure - Donders Institute

Table of contents

- 1. purpose

- 2. expert guidelines

- 3. stimulation protocols

- 4. procedures

- 5. risk, safety and burden

- 6. appendices

- 7. References

- 8. License

1. purpose

This procedure is intended to ensure that non-invasive brain stimulation studies (using TUS) are consistently conducted in accordance with local ethical regulations and international consensus regarding risk and safety.

2. expert guidelines

All certified users and those who plan to use NIBS techniques need to be familiar with the expert guidelines on safety and use of the respective techniques, where available. Minimal required reading for TUS includes: “Ultrasound neuromodulation: A review of results, mechanisms, and safety” (Blackmore et al., 2019); as well as “Safety of transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation: A systematic review of the state of knowledge from both human and animal studies” (Pasquinelli et al., 2019); and “A retrospective qualitative report of symptoms and safety from transcranial focused ultrasound for neuromodulation in humans” (Legon et al., 2020).

3. stimulation protocols

Stimulation protocols for TUS can be categorized by the duration and neurophysiological mechanisms of the effect (online, short-term, long-term). In a single study more than one stimulation protocol can be employed. Importantly, the nature of a study is always classified according to the effects of the study as a whole, not of individual stimulation protocols. For more information refer to appendix A.

- online: these protocols rely on immediate excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms that have only instantaneous effects (≤1 sec). Examples: pulse or burst TUS protocols (≤1 sec).

- short-term: these protocols rely on transient functional modulations of synaptic efficacy that have short-lasting effects (>1 sec, ≤3 hours). Examples: repetitive or patterned TUS (>1 sec).

- medium-term: these protocols rely on slow but transient modulations of synaptic efficacy that have medium-term effects (>3 hours, ≤1 week). These protocols typically capitalize upon physiological mechanisms of plasticity with tailored parameters or aim to induce cumulative effects by repeating sessions.

- long-term: these protocols rely on slow structural modulations of synaptic function* that have long-lasting effects (>1 week).** These stimulation protocols always entail repeated sessions (e.g. daily) over a prolonged period (e.g. weeks) with typically high-quantity, high-intensity and/or high-frequency pulse delivery.

- other: these protocols do not meet any of the above criteria and/or the effects are*** not yet well-known. In general, the procedures for long-term stimulation protocols apply, except if all stimulation parameters (including intensity, frequency and quantity) are similar or lower than those of existing online, short-term, or medium-term stimulation protocols, in which case the respective procedures apply.

4. procedures

4.1. screening

Before each experiment session, participants will be screened on possible exclusion criteria using a screening questionnaire. This questionnaire is based on a published international non-invasive brain stimulation safety consensus report (Rossi et al., 2011). In addition to these standardized questions, potential participants are asked whether they have participated in a non-invasive brain stimulation study before. If they respond positively, they are asked about the specifics and time of their last study, and whether they have experienced problems related to their participation in previous studies.

This information is used by the designated certified experimenter to decide whether the participant will be included in the study. In case any questions on the procedure arise, the experimenter can contact the certified lab support staff and institute consultant. In case of any doubt with regard to medical issues, the responsible physician will be consulted. If the certified experimenter or responsible physician has any concerns or doubts regarding the safety of the participants or their ability to follow the required experimental procedures the candidate participant is excluded from participation.

4.2. exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria for non-invasive brain stimulation sessions are defined in the MREC approved study protocol. Accordingly, sessions falling under a general DCCN or DCC CMO study protocol will adhere to the latest version of the standardized Donders exclusion criteria screening questionnaires. All other approved studies can accommodate study-specific changes to these standardized exclusion criteria.

The certified experimenter will decide upon inclusion or exclusion of the prospective participant. Unless otherwise stated, it is the norm that participants will be excluded from the session if they meet at least one of the following criteria:

- Under 18 years of age

- Current or planned pregnancy

- A history or brain surgery or serious head trauma

- A history of or any close relatives (parents, siblings, children) with epilepsy, convulsion, or seizure

- Predisposition for fainting spells (syncope)

- A cardiac pacemaker or intra-cardiac lines

- An implanted neurostimulator

- Implanted medication infusion device

- Implanted metal devices or large ferromagnetic fragments in the head or upper body (excluding dental wire), or jewellery/piercing that cannot be removed

- Use of a medical plaster that cannot or may not be taken off (e.g., nicotine plaster)

- Cochlear implants

- Metal in the brain, skull, or elsewhere in your body (fragments, clips, etc.)

- Diagnosed neurological or psychiatric disorders

- Use of psychoactive (prescription) medication (excluding anti-conception)

- Skin disease at intended stimulation sites

- The consumption of more than four alcoholic units within 24 hours before participation or any recreational drugs within 48 hours before participation

4.3. monitoring adverse events

All observed and reported adverse events are followed until they have abated, or until a stable situation has been reached. When the event concerns the health of the participants, the responsible physician will be consulted. All adverse events are reported in detail to the clinical research coordinator and the institute consultant. In the unlikely scenario of a serious adverse events, the sponsor and MREC will be informed without undue delay.

4.3.1. online, short-term, and medium-term studies

All participants fill in the side-effect questionnaire at the end of the stimulation session. In case an adverse event is observed or reported, the participant is always contacted for further inquiry within 7 days after the stimulation session. There is no follow-up on participants when no adverse event was observed or reported.

4.3.2. reporting adverse events

In the unlikely case of an adverse event, the following must be reported as soon as possible to the clinical research coordinator and the institute consultant:

- Occurrence

- Study code

- Participant code

- Date

- Time

- Description

- Type of event (fainting, headache, etc.)

- The situation of the event (e.g. during intake, during task, etc.)

- Prior history of similar incidents in this person

- Other relevant details (e.g. participant reported being nervous, room temperature was high, light intensity was strong, participant looked pale, etc.)

- Intensity

- Severity of event

- Duration of event

- Relatedness

- Plausible relationship to study intervention

- The stimulation protocol

- The timing of the event in relation to the stimulation protocol

- Action taken

- The specific action that has been taken to aid the participant

- Whether additional assistance was acquired (e.g. second experimenter, GP, emergency help (55555 or 112)).

- How long the care of the participant lasted

- How the participant left the experiment (e.g., the participant was able to leave without assistance; a friend or family member was contacted to pick up the participant; etc).

5. risk, safety and burden

5.1. assessment of risk, safety, and burden

Assessment of risk, safety, and burden of a study is best safeguarded by ensuring relevant expertise and knowledge is available at the institute, not by putting undue confidence in arbitrary thresholds and parameters. Namely, the efficacy and safety of a stimulation protocol depends on the interaction of numerous parameters. It is expert consensus that no fixed boundaries can be set for any of these parameters in isolation, neither based on empirical evidence nor scientific reasoning. We aim to update this SOP when new evidence and guidelines become available following international expert consensus.

Relevant parameters for TUS are, for example, pressure (MPa), ultrasound frequency (Hz), pulse length (ms), pulse repetition frequency (Hz), stimulation duration (s), duty cycle (%), and parameters relevant to safety such as peak rarefaction pressure (MPa), temperature rise (°C), thermal dose (CEM43°C), and total energy deposited, and parameters relevant to relate the protocol to other studies and guidelines for diagnostic ultrasound, such as intensity (e.g. Isppa, Ispta), mechanical index (MI), and the thermal index of the cranium (TIC).

5.2. Safety of online, short-term, and medium-term studies

Please find a synopsis of the risk, safety and burden assessment of online, short-term, and medium-term non-invasive brain stimulation studies below; for more information see appendix B.

5.2.1. TUS studies

Transcranial ultrasonic stimulation (TUS) is an emergent non-invasive brain stimulation technique (Fomenko et al., 2018; Tyler, Lani and Hwang, 2018; Kamimura et al., 2020). Unlike TMS and TES, it does not utilise electromagnetic fields to deliver energy, but rather employs mechanical forces to achieve neuromodulation (Blackmore et al., 2019; Jerusalem et al., 2019). The most likely mechanism of action is acoustic radiation force (ARF) affecting ion channel gating and membrane capacitance (Blackmore et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2020). During stimulation, participants may hear a soft buzzing or tone and experience weak tactile sensations, depending on the transducer mechanics and sonication protocol. Sometimes a light transient headache and a feeling of fatigue is reported, although it is not clear whether these are caused by the stimulation or participation in the experiment (Legon et al., 2020).

Ultrasound is a well-established technique for diagnostic imaging, including transcranial imaging. However, transcranial stimulation for neuromodulation is an emergent application of this technique, and there are currently no expert consensus guidelines published specifically for transcranial ultrasonic neuromodulation. Therefore, prior research has often adopted guidelines for diagnostic ultrasound from regulatory bodies, for example, the United States Food and Drugs Administration (FDA, 2019) and British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS, 2010). These guidelines are designed to control the two main bioeffects of diagnostic ultrasound, mechanical and thermal effects, through reasonable proxy parameters. At the Donders Institute, we extend this approach to ‘informed risk aversion’, using validated simulations of mechanical and thermal effects to assess the risk of TUS studies in relation to expert consensus on thermal dose and safety in human participants.

Published meta analyses based on the available data suggest that TUS in humans is safe where stimulation parameters resemble those of previous research, with limited intensity and duration (Blackmore et al., 2019; Pasquinelli et al., 2019; Legon et al., 2020). Based on published data and biophysical considerations, informed by guidelines on safety of diagnostic ultrasound and thermal dose, supplemented by biophysical simulations, local experts consider the additional risk and burden associated with participation to be minimal and no serious adverse events are expected for online, short-term, and medium-term TUS studies.

5.2.2. Studies combining different techniques

NIBS techniques can be safely combined with other NIBS and neuroimaging techniques. These combinations, such as TMS or TUS together with EEG, might add to logistical and technical complexity, but are unlikely to change the safety assessments beyond those for the techniques individually. However, for some, such as combining TES with fMRI, additional care is warranted. Here, we follow dedicated expert consensus guides (Esmaeilpour et al., 2020).

6. appendices

6.1. appendix A: supplementary information on TUS

6.1.1. transcranial ultrasonic stimulation (TUS)

Transcranial ultrasonic stimulation (TUS) is an emergent form of non-invasive brain stimulation that is unique in both its ability to stimulate deep brain structures and its high spatial resolution (Fomenko et al., 2018; Tyler, Lani and Hwang, 2018; Kamimura et al., 2020). Unlike other forms of NIBS (i.e., TMS and TES) that employ electromagnetic fields to achieve neuromodulation, TUS delivers mechanical forces through sound waves at a frequency beyond human hearing (Blackmore et al., 2019).

Online TUS protocols often use stimulus durations between 200-500 ms. They result in near-immediate effects of TUS on neuronal activity (online, < 1 sec). Repetitive or patterned application of TUS can further modulate neuronal activity, transiently outlasting the period of stimulation itself (short-term, > 1 sec, < 3 hours). Both online and short-term TUS can be combined in a single experiment. To date, there are no overtly observable effects of TUS in humans (Ai et al., 2018; Legon, Bansal, et al., 2018; Fomenko et al., 2020), like the muscle twitch that can be evoked in response to TMS. Nevertheless, the effects can be quantified by a wide variety of measures, for example, by behavioural performance, neuroimaging techniques such as EEG and fMRI, physiological measures such as modulation of the MEP, or skin-conductance response. It is worthwhile to note here that mechanical stimulation, compared to electromagnetic stimulation, comes with the benefit of less interference during EEG and fMRI recordings.

The effect of TUS on a brain circuit depends on the interaction between stimulation parameters, neurophysiology, and the neural state of the circuit. Relevant stimulation parameters are pulse duration, pulse repetition frequency, burst duty cycle, and more (Fomenko et al., 2020). Depending on these parameters and their interactions with physiology and neural state, TUS may induce only transient online effects, or may result in longer lasting short-term effects (Fomenko et al., 2020). For neuromodulation in human participants, low-intensity ultrasound waves (i.e., a spatial-peak pulse average of 1-28 W/cm2) within the lower ultrasound range (i.e., 200-1000 kHz) are applied. The parameters often fall within the domain designated as safe for diagnostic ultrasound by the FDA (FDA, 2019) and there have been no serious adverse effects of TUS in any human application (Pasquinelli et al., 2019; Legon et al., 2020).

6.1.2. mechanisms of neuromodulation by TUS

The two main bioeffects of focused ultrasound are of mechanical and thermal nature. We will discuss their relevance for safety in Appendix B. In this section we will focus on their relevance for neuromodulation. While both thermal and mechanical mechanisms for neuromodulation exist, this SOP is limited to the pertinent mechanical neuromodulation in the non-thermal domain.

Ultrasound waves can be focused at a desired target location, much like light waves can be focused by a magnifying glass. This allows targeting of a given brain region with millimeter precision without interfering with neural activity at intermittent locations. One prominent mechanical force of focused ultrasound is known as the ‘acoustic radiation force’. This force does not fluctuate at the ultrasound frequency itself (as the pressure waves do), but rather this force changes with the amplitude envelope of the ultrasound, being constant at a constant acoustic intensity. This force therefore fluctuates with the pulse repetition frequency, or more precisely, with the amplitude envelope, rather than at the fundamental frequency.

It is proposed that the acoustic radiation force generated by TUS affects mechano-sensitive ion channel gating as well as membrane capacitance (Blackmore et al., 2019; Jerusalem et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2020). Concerning mechano-sensitive ion channels, TUS activates these channels, leading to calcium influx, subsequently triggering a signaling cascade, and eventually culminating in activation of voltage-gated ion channels that directly modulate neural activity (Yoo et al., 2020). Models of neural modulation that do not rely on ion-channel gating have been proposed. For example, membrane volume changes resulting from TUS and the flexoelectric effect may play a role in changing membrane capacitance directly (Jerusalem et al., 2019). It is important to consider here that the ultimate effects of TUS may be excitatory or inhibitory, depending on factors such as the state and circuit dynamics of the stimulated neuronal population.

6.1.3. TUS parameters

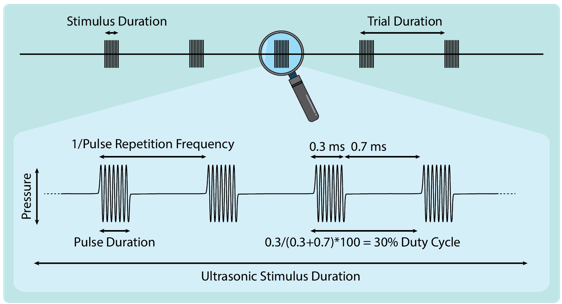

Multiple stimulation parameters are relevant to the application of TUS. These include, but are not limited to: peak rarefaction pressure (Pr), ultrasound frequency, pulse repetition frequency, duty cycle, pulse duration, ultrasonic stimulus duration, and trial duration (see figure 1).

A pulse is defined as the shortest continuous administration of ultrasound. An ultrasonic stimulus is defined as the largest singular grouping of ultrasound administration uninterrupted by substantial breaks, such as an inter-trial interval. An ultrasonic stimulus can consist of a single continuous sonication, a train of pulses at a pulse repetition frequency, or patterned pulses. The duty cycle represents the proportion of time during the stimulus duration where ultrasound is delivered (i.e., the percentage of pulse on-time). Given the aforementioned parameters, and appropriate simulations or measurement, indices relevant to TUS safety can be derived: the peak rarefaction pressure (Pr), the temperature rise (TR), the thermal dose in cumulative equivalent minutes (CEM43°C), and the total energy deposited. Additional indices can be derived for comparison to published guidelines for diagnostic ultrasound (BMUS, 2010; FDA, 2019). These include the spatial-peak pulse-averaged intensity (Isppa, the average intensity of an individual pulse), the spatial-peak temporal-averaged intensity (Ispta, the average intensity over the ultrasonic stimulus duration), the mechanical index (MI), and the thermal index of the cranium (TIC). The spatial-peak temporal-averaged intensity (Ispta) is calculated conservatively, averaging over the duration of the ultrasonic stimulus.

Figure 1. TUS parameters. Visual representation of common TUS parameters including stimulus duration, trial duration, pulse repetition frequency, pulse duration, duty cycle, and pressure.

6.1.4. online TUS

TUS protocols for which the effects are only present during the stimulation period, for example simultaneously with a task or neuroimaging session, are referred to as ‘online’. Online TUS is mainly used to transiently modulate ongoing neural activity relevant to the behavioral or cognitive processes under investigation, but may also be used to influence, for example, primary motor cortex excitability (Ai et al., 2018; Legon, Ai, et al., 2018; Fomenko et al., 2020).

6.1.5. short-term and medium-term TUS

TUS protocols for which the effects transiently outlast the stimulation period for up to 3 hours are referred to as ‘short-term’. These protocols are sometimes characterized by longer pulse durations (e.g., 1-30 ms) applied in a longer train that may last around 20 seconds or more. For TUS, short-term stimulation protocols usually serve to transiently induce neuroplastic mechanisms leading to, e.g., changes in primary motor cortex excitability or transiently altered interregional connectivity. Short-term TUS protocols are established in non-human primate studies (Verhagen et al., 2019), and emergent in human applications (Fomenko et al., 2020; Sanguinetti et al., 2020). TUS protocols for which the effects transiently outlast the stimulation period by more than 3 hours, but without lasting structural changes, are referred to as ‘medium-term’. Such protocols have been proposed but are not yet widely adopted.

6.1.6. multifocal TUS

Sometimes, it is desirable for TUS to be applied to multiple brain regions during the same experiment. This may take the form of testing whether region A, but not control site region B, is relevant to a particular cognitive function. Alternatively, it could be to test how connected regions A and B might interact concerning a particular cognitive function. Yet another alternative is when an experimenter may wish to stimulate two brain regions simultaneously, for example if one wishes to stimulate both amygdalae. For all three cases, but particularly the latter, special consideration must be taken concerning safety (e.g., controlling the total acoustic energy delivered, thermal dose, and potentially wave interference).

6.2. appendix B: safety, risk and burden assessment for NIBS

6.2.1. transcranial ultrasonic stimulation (TUS)

Transcranial ultrasonic stimulation is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique based on mechanical stimulation achieved through ultrasound waves. During stimulation, participants may hear a soft buzzing or tone and experience weak tactile sensations, depending on the transducer mechanics and sonication protocol. All reported side-effects of TUS are transient and occur during or immediately after the stimulation session (Legon et al., 2020).

The two main bioeffects of ultrasound relevant for safety assessment are thermal and mechanical bioeffects. Concerning thermal bioeffects, when ultrasonic waves travel through tissue mechanical energy can be transferred to thermal energy through absorption, leading to tissue heating. Absorption is often higher in bone tissue, and the thermal dose increases with longer durations. Stimulation parameters relevant for the assessment of the safety, risk and burden of online and short-term TUS studies in relation to the thermal bioeffects are the acoustic intensity, thermal index, and stimulation duration (Blackmore et al., 2019). Concerning mechanical bioeffects, rapid changes in local pressure can lead to acoustic cavitation: the formation, oscillation, and at extreme pressures, collapse of microcavities of vacuum or vapor due to ultrasonic waves travelling through tissue, resulting in mechanical bioeffects. With higher intensities, the mechanical risk increases. Stimulation parameters relevant for the assessment of the safety, risk and burden of online and short-term TUS studies in relation to the mechanical bioeffects are peak negative pressure, frequency, and stimulation duration (Blackmore et al., 2019).

Importantly, these bioeffects of ultrasound are ‘threshold effects’. At low levels their risk is negligible, and only above a threshold does the risk increase with increasing dose. Concerning temperature, at low thermal dose, the temperature stays within the physiological range and there is no risk for damage. Concerning cavitation, this only occurs at sufficient peak negative pressures. Cavitation is absent at lower pressures (for example, below 2 MPa), while at moderate pressures, as conventionally used for diagnostic ultrasound imaging, microscopic bubbles might oscillate in a stable fashion. Only at more extreme negative pressures (for example, beyond 4 MPa) can bubbles collapse, so called ‘inertial cavitation’. This can be contrasted against, for example, radiation, where even low-intensities are damaging to some extent. The most important factor to ensure safety, therefore, is to ensure thermal and mechanical bioeffects are indeed limited to the safe domain.

Side-effects of online and short-term TUS protocols are uncommon, but sometimes a light transient headache and a feeling of fatigue is reported. Importantly, it is not clear whether these are caused by the stimulation or simply by participation in the experiment (Legon et al., 2020). All reported side-effects of TUS are transient and occur during or immediately after the stimulation session and no serious adverse effects of TUS have been observed in humans (Blackmore et al., 2019; Pasquinelli et al., 2019; Legon et al., 2020). Mild or moderate symptoms have been reported, including a mild headache and neck pain, where participants felt these were possibly or probably related to the TUS experiment (Legon et al., 2020). However, this initial report does not compare verum versus sham TUS, limiting interpretation of the reported symptoms as stemming from stimulation versus the common burden of participating in an experiment that requires sustained attention and minimal movement. Regardless of etiology, these reports are similar to the mild adverse effects reported following TMS or TES (Nitsche et al., 2008; Rossi et al., 2020), and subsided at follow-up questioning. Notably, there are no immediate adverse effects of TUS during stimulation such as the prickling that can be experienced during TES or the facial contractions during TMS (Legon et al., 2020).

The majority of animal studies have similarly reported few adverse effects (Blackmore et al., 2019; Pasquinelli et al., 2019; Gaur et al., 2020), though serious adverse effects were observed in a small number of studies where stimulation parameters were beyond acceptable limits for human application. Systematic reviews have highlighted potential findings that are surprising and require follow-up investigations (see Blackmore et al., 2019; Pasquinelli et al., 2019). For example, more recent histology research using control conditions has highlighted that TUS at higher intensities than applied in humans does not result in tissue damage in large animal models (i.e., sheep and macaque monkeys; Gaur et al., 2020), and that previous findings of micro-hemorrhages are likely attributable to post-mortem brain extraction rather than effects of TUS (Gaur et al., 2020).

Considering TUS is a relatively new form of non-invasive brain stimulation, it is relevant to be informed by the more established inclusion and exclusion criteria as available for TMS and TES, even when a potential risk of TUS is currently only a theoretical possibility. For example, there is a theoretical possibility that some tissues or objects can cause disturbance in acoustic wave propagation, cause unexpected absorption leading to thermal rise, or can experience undesirable displacement forces. Accordingly, adopting TMS and TES criteria, large or ferromagnetic metal parts in the head or near the stimulation site are generally exclusion criteria for TUS. For example, we generally exclude patients with a neurostimulator such as used for deep brain stimulation, while we allow participants with a dental wire behind the teeth. Further, although the risk for an epileptic seizure following TUS is unknown, TUS is known to modulate neuronal excitability. Consequently, for studies in the healthy population, guidelines will be followed concerning susceptible populations, that is, participants at increased risk for seizure, with direct family with epilepsy, or participants taking medication that affects brain excitability will not be permitted to participate. Please note that these procedures are not yet based on evidence. In fact, specific TUS protocols are being investigated for their potential to prevent and inhibit epileptic seizures. As such, these procedures are dependent on the study protocol, population, and aim.

Formal expert consensus on safety standards for TUS have not yet been published. Local experts consider the additional risk of a TUS study protocol minimal when the peak rarefaction pression is <2 MPa, the temperature rise <1 °C for the brain and <2 °C for the skull, and the total energy deposited is comparable to previously published studies. For full details on existing regulations and consensus, and the approach to ensure safety at the Donders Institute, please see below.

Currently, there are no regulatory guidelines for manufacturers of equipment intended for transcranial ultrasonic stimulation in humans. Indeed, most equipment suitable for TUS applications sold in the European Economic Area does not have CE marking to signify they meet safety, health, and environmental protection requirements. Following European Medical Device Regulations and Dutch national law (WMO), human study proposals that intend to make use of non-CE-marked equipment should be accompanied by an ‘Investigational Medical Device Dossier’ (IMDD). The IMDD specifies all items of the non-CE-marked medical device and its software that must be covered for an application to the MREC. The IMDD includes a comprehensive description and specification of the device and its items, manufacturer and manufacturing information, safety and performance requirements, benefit-risk analysis and risk management, and product verification and validation.

All subjects are screened for their relevant medical history and other aspects concerning the safety of TUS application. All investigators involved are well-trained and qualified (as ensured by the certified experimenter system at the Donders Institute), and the equipment used adheres to the required international safety standards (IEC 60601). In summary, the risk and burden associated with participation can be considered minimal and no serious adverse events are expected during online and short-term TUS studies.

6.2.2. existing regulations and consensus on TUS safety

Currently, there is no formal expert consensus on safety standards for the application of TUS. However, relevant societies, foundations, and regulatory bodies, including the Focused Ultrasound Foundation (FUSF), the International Society for Therapeutic Ultrasound (ISTU), the IEEE Ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control society (IEEE-UFFC), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are supporting an international consortium comprised of dozens of experts to establish consensus on these matters. Donders experts are ensured to remain knowledgeable of the latest expert consensus by means of active participation in the consensus meetings.

In lieu of TUS-specific consensus guidelines at the present time, research at the Donders Institute will adhere to the safety standards for diagnostic ultrasound published by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2019 “Marketing Clearance of Diagnostic Ultrasound Systems and Transducers”, Section 5.2.7 Table 3 and Section 5.2.7.1.4). These guidelines are validated in the context of diagnostic ultrasound imaging, including human transcranial applications, and can be considered applicable for transcranial ultrasonic stimulation in humans. Regulatory bodies have set guidelines and upper boundaries for indices of mechanical and thermal bioeffects. The FDA reports that an estimate of maximum temperature rise should be provided concerning thermal bioeffects. Safe levels of temperature rise and dose in humans, including transcranial applications, are specified by the European guidelines for magnetic resonance radiofrequency exposure (MRI + EUREKA consortium; van Rhoon et al., 2013). At all times we will adhere to safety regulations as reported by the FDA and the MRI + EUREKA consortium. The relevant parameters from international guidelines are presented in table 1.

Table 1 International guidelines relevant for (diagnostic) transcranial ultrasound

| Bioeffects | Index | Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Isppa | ≤190 W/cm2* |

| MI | ≤1.9* | |

| Thermal | Ispta | ≤720 mW/cm2 |

| if Ispta > 720 mW/cm2 | “Provide an estimate of maximum temperature rise (TR) attributable to the use of that transducer […] describe the model used to determine estimation […] should account for heating of skull bone”* | |

| TR | <2 °C in healthy participants, without medical doctor or trained response present** |

*Guideline from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); Guideline from the European MRI + EUREKA consortium (MRI radiofrequency exposure levels)

While parameters specified by FDA guidelines are a remote proxy of safety, and the European MRI thermal dose parameters are originally designed for radiofrequency exposure, they are valuable for transcranial ultrasound applications nonetheless. Namely, these parameters are extensively validated in the context of biomedical ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging and are historically used as an informal benchmark for neuromodulation applications of low-intensity ultrasound.

Concerning mechanical bioeffects, the TUS equipment at the Donders Institute is limited to an Isppa of 30 W/cm2 in free water, which will result in an intracranial Isppa below 30 W/cm2, far below the FDA upper boundary of 190 W/cm2. Using simulations of acoustic wave propagation, we will minimize the risk of mechanical bioeffects by ensuring the acoustic peak rarefaction pressure is kept below 2 MPa.

Concerning thermal bioeffects, the TUS equipment at the Donders Institute is limited to an Ispta of 15 W/cm2 in free water. To further minimize risks of thermal bioeffects, as per FDA regulations, we will use acoustic and thermal simulations to estimate the maximum temperature rise. While no limit of TR is given by the FDA, MRI RF thermal exposure parameters provide an extensively validated guideline in the context of biomedical ultrasound and MR imaging. Here, we will limit TR to 2 °C for the skull and 1 °C for brain tissue, as demonstrated by thermal simulations.

6.2.3. Informed stepwise approach to TUS safety

To ensure thermal safety, stimulation must be in adherence to FDA regulation. In practice, this means that temperature rise must be limited. Hereafter follows an explanation of how safe levels of temperature rise can be demonstrated, per FDA regulation.

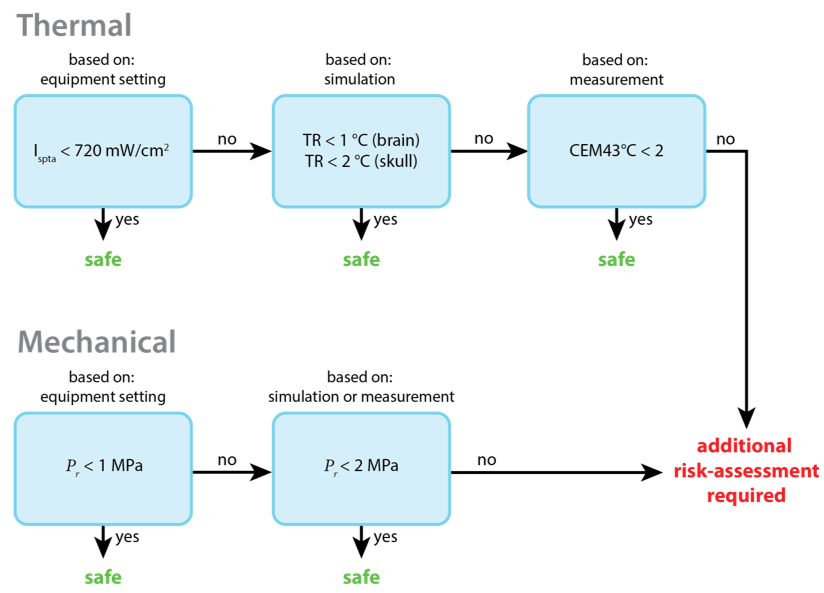

With an Ispta below 720 mW/cm2, based on the stimulation parameters as reported by the equipment, thermal risk is contained and no further thermal risk assessment is required. In the common scenario that stimulation intensities exceed this threshold, acoustic and thermal modelling accounting for the presence of the skull is conducted to derive an informed estimate of maximum temperature rise (TR) (FDA, 2019). This modelling is achieved with a combination of skull imaging (either MRI or CT), skull segmentation (e.g., with SimNIBS), an acoustic model, and finally a thermal model in k-Wave (i.e., a MATLAB toolbox for acoustic and thermal simulations). A conservative threshold for temperature rise is set at TR < 1 °C for the brain and TR < 2 °C for the skull. Below this threshold, temperature rise is deemed safe for any tissue type, not only in healthy participants but also in patients with compromised thermoregulation, and without requirement for a medical doctor or a dedicated trained person present to respond instantly to heat-produced physiological stress (van Rhoon et al., 2013). When the temperature rise briefly exceeds this limit, thermal damage risk is better assessed in the context of thermal dose (TD), as measured in cumulative equivalent minutes relative to one minute at 43°C (CEM43°C). This measure of thermal effects incorporates both temperature level and exposure length. In healthy participants, without medical or trained response present, the thermal dose should be smaller than 2 CEM43°C (van Rhoon et al., 2013). Thermal dosage exceeding this threshold are beyond the scope of this SOP and require separate risk assessment. A graphical depiction of the informed stepwise approach to demonstrate thermal safety is provided in figure 2

A similar informed stepwise approach is taken to demonstrate mechanical safety. Specifically, with a peak rarefaction pressure (Pr) below 1 MPa, based on the stimulation parameter as reported by the equipment, no further mechanical risk assessment is required. In the scenario that stimulation pressures exceed this threshold, a further informed estimate of the peak rarefaction pressure acoustic is derived from measurement or modelling accounting for the presence of the skull. A conservative threshold for acoustic pressure is set at Pr < 2 MPa. Below this threshold, mechanical bioeffects are deemed safe for any tissue type. Stimulation pressures exceeding this threshold are beyond the scope of this SOP and require separate risk assessment. A graphical depiction of the informed stepwise approach to demonstrate mechanical safety is provided in figure 2.

Figure 2. Informed stepwise approach to thermal and mechanical safety. The thermal risk (top row) is considered minimal if Ispta is below 720 mW/cm2. For higher intensities, the maximum temperature rise (TR) must be measured or estimated using acoustic and thermal simulations. If the TR is below 1°C in the brain and below 2°C in the skull, the thermal risk is considered minimal. For higher peak temperature rise, the thermal dose must be estimated based on measurements. When the CEM43°C is below 2, the thermal risk is considered minimal. For higher dosages, additional risk-assessments are required. The mechanical risk (bottom row) is considered minimal if the peak rarefaction pressure is below 1 MPa, when relying on equipment settings, or below 2 MPa, when measured or simulated with validated acoustical models. For higher pressures, additional risk-assessment is required.

Please note that safety assessment of transcranial ultrasonic stimulation is reliant on accurate estimations and measurements of acoustic pressure and thermal effects. These can be approximated by validated acoustic and thermal simulations. Indeed, this informed approach forms the back-bone of safety assessment of TUS at the Donders Institute.

6.2.4. Informed risk aversion

To ensure safety, an approach of ‘informed risk aversion’ is taken at the Donders Institute. That is, within the boundaries of the available safety-relevant data, conservative estimates of safety parameters are made. Therefore, by default, acoustic and thermal simulations incorporate as much participant, session, and stimulation specific information as available to make an accurate estimation of safety. Where such information is not available or uncertain, we adopt conservative (‘worst-case’) estimates of parameters and circumstances to guard safety. In practice, this means that with little information available, acoustic intensities and durations are considerably limited. When permitted by more information and less uncertainty, higher intensities and longer durations can be applied while ensuring the same minimal risk. As such, this approach is known as ‘informed risk-aversion’.

Validated acoustic and thermal simulations yield an estimation of impact and risk of TUS, beyond remote proxy parameters. These simulations are necessary for the estimation of safety-relevant measures such as acoustic pressure (Pr) and temperature rise (TR) for the skull and brain tissue. These simulations also help to compare planned TUS protocols to previous studies that report indices relevant for diagnostic ultrasound, such as spatial-peak pulse- and temporal-average intensities (Isppa and Ispta), the mechanical index (MI), and the thermal index of the cranium (TIC). Importantly, simulations also assist in planning accurate TUS target engagement. Therefore, running acoustic and thermal simulations before stimulation is standard practice at the Donders Institute.

An approach of ‘uninformed risk aversion’ has been implemented in previous research by adopting acoustic parameters of such low intensity that they are deemed safe in all conditions, even without any knowledge of individual safety parameters (e.g., transducer positioning, skull thickness, bulk modulus). This approach has proven successful. However, it does not minimize the risk of under-dosing, and it does not account for inter-individual variation. To maximize safety and consistency while minimizing the risk of under-dosing, uncertainty about the simulation must be reduced, including uncertainty about source pressure, absorption, wave propagation, skull properties, and more. Thus, the ‘informed risk-aversion’ approach can be followed by making conservative estimates where there is uncertainty, while aiming to minimize this uncertainty through, for example, individualized skull imaging, simulations, and neuronavigation.

6.2.5. simulations for TUS

Simulations of acoustic wave propagation and temperature dynamics can return parameters relevant to the safety of a TUS protocol. Several validated software packages are available for this purpose. At the Donders, we often use the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox to run these simulations. This toolbox has previously been validated (Treeby and Cox, 2010; Treeby et al., 2012, 2018; Wang et al., 2012; Demi, Treeby and Verweij, 2014; Martin, Ling and Treeby, 2016; Top, White and McDannold, 2016; J. L. B. Robertson et al., 2017; J. Robertson et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2018; Martin, Jaros and Treeby, 2020; McDannold, White and Cosgrove, 2020; Ozenne et al., 2020). When available, individual skull data will be used to run subject-specific models. Acoustic properties such as density (Kg/m3), sound speed (ms-1), and absorption rate parameters of the various media in the head (i.e., the skull, CSF, blood or water) are taken from the literature, or approximated from the available scan based on conversion from Hounsfield Units (HU) following calibration as reported in the literature. An ‘informed risk aversion’ approach will be used, where conservative estimates of parameters relevant to safety will be made within the boundaries of what we do know. Often, the skull data is combined with an anatomical MRI to determine the location and geometrically arrange boundaries between media relevant to the acoustic stimulation.

The acoustic simulation is run until the simulation reaches steady state and simulation convergence is achieved. The resultant pressures are subsequently used to determine the volume rate of heat deposition. The initial temperature of the system is set at 37 °C. Further, sound speed, density, thermal conductivity [W/(m K)] and specific heat [J/(kg K)] are specified based on literature values. Sonication parameters are set following protocol, including: total ultrasonic stimulation time, pulse duration, pulse repetition frequency, burst duration, burst duty cycle, and trial duration. Together the acoustic and thermal simulations are used to provide global and local estimates Pr, TR, TD, total energy deposited, and of Isppa and Ispta, supplemented by MI and TIC. Only when, based on the outcome of simulations, we can ensure the minimal risk of thermal and mechanical bioeffects will TUS be applied.

7. References

Ai, L. et al. (2018) ‘Effects of transcranial focused ultrasound on human primary motor cortex using 7T fMRI: a pilot study’, BMC Neuroscience, 19(1), p. 56. doi: 10.1186/s12868-018-0456-6.

Blackmore, J. et al. (2019) ‘Ultrasound Neuromodulation: A Review of Results, Mechanisms and Safety’, Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, 45(7), pp. 1509–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.12.015.

BMUS (2010) ‘Guidelines for the safe use of diagnostic ultrasound equipment, Safety Group of the British Medical Ultrasound Society’, 18(2), pp. 52–59. doi: 10.1258/ult.2010.100003.

Demi, L., Treeby, B. E. and Verweij, M. D. (2014) ‘Comparison between two different full-wave methods for the computation of nonlinear ultrasound fields in inhomogeneous and attenuating tissue’, in 2014 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium. 2014 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, pp. 1464–1467. doi: 10.1109/ULTSYM.2014.0362.

Esmaeilpour, Z. et al. (2020) ‘Methodology for tDCS integration with fMRI’, Human Brain Mapping, 41(7), pp. 1950–1967. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24908.

FDA (2019) ‘Information for manufacturers seeking marketing clearance of diagnostic ultrasound systems and transducers’, Document issued September 9, 2008, Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health., U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/marketing-clearance-diagnostic-ultrasound-systems-and-transducers (Accessed: 7 December 2020).

Fomenko, A. et al. (2018) ‘Low-intensity ultrasound neuromodulation: An overview of mechanisms and emerging human applications’, Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, 11(6), pp. 1209–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.08.013.

Fomenko, A. et al. (2020) ‘Systematic examination of low-intensity ultrasound parameters on human motor cortex excitability and behaviour’, eLife. Edited by L. Dugué, 9, p. e54497. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54497.

Gaur, P. et al. (2020) ‘Histologic safety of transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation and magnetic resonance acoustic radiation force imaging in rhesus macaques and sheep’, Brain Stimulation, 13(3), pp. 804–814. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.02.017.

Jerusalem, A. et al. (2019) ‘Electrophysiological-mechanical coupling in the neuronal membrane and its role in ultrasound neuromodulation and general anaesthesia’, Acta Biomaterialia, 97, pp. 116–140. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.07.041.

Kamimura, H. A. S. et al. (2020) ‘Ultrasound Neuromodulation: Mechanisms and the Potential of Multimodal Stimulation for Neuronal Function Assessment’, Frontiers in Physics, 8. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.00150.

Legon, W. et al. (2014) ‘Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans’, Nature Neuroscience, 17(2), pp. 322–329. doi: 10.1038/nn.3620.

Legon, W., Ai, L., et al. (2018) ‘Neuromodulation with single-element transcranial focused ultrasound in human thalamus’, Human Brain Mapping, 39(5), pp. 1995–2006. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23981.

Legon, W., Bansal, P., et al. (2018) ‘Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of the human primary motor cortex’, Scientific Reports, 8(1), p. 10007. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28320-1.

Legon, W. et al. (2020) ‘A retrospective qualitative report of symptoms and safety from transcranial focused ultrasound for neuromodulation in humans’, Scientific Reports, 10(1), p. 5573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62265-8.

Martin, E., Jaros, J. and Treeby, B. E. (2020) ‘Experimental Validation of k-Wave: Nonlinear Wave Propagation in Layered, Absorbing Fluid Media’, IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 67(1), pp. 81–91. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2019.2941795.

Martin, E., Ling, Y. T. and Treeby, B. E. (2016) ‘Simulating Focused Ultrasound Transducers Using Discrete Sources on Regular Cartesian Grids’, IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 63(10), pp. 1535–1542. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2016.2600862.

McDannold, N., White, P. J. and Cosgrove, R. (2020) ‘Predicting Bone Marrow Damage in the Skull After Clinical Transcranial MRI-Guided Focused Ultrasound With Acoustic and Thermal Simulations’, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39(10), pp. 3231–3239. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.2989121.

Nitsche, M. A. et al. (2008) ‘Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008’, Brain Stimulation, 1(3), pp. 206–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004.

Ozenne, V. et al. (2020) ‘MRI monitoring of temperature and displacement for transcranial focus ultrasound applications’, NeuroImage, 204, p. 116236. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116236.

Pasquinelli, C. et al. (2019) ‘Safety of transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation: A systematic review of the state of knowledge from both human and animal studies’, Brain Stimulation, 12(6), pp. 1367–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.07.024.

van Rhoon, G. C. et al. (2013) ‘CEM43°C thermal dose thresholds: a potential guide for magnetic resonance radiofrequency exposure levels?’, European Radiology, 23(8), pp. 2215–2227. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2825-y.

Robertson, J. et al. (2017) ‘Sensitivity of simulated transcranial ultrasound fields to acoustic medium property maps’, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 62(7), pp. 2559–2580. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa5e98.

Robertson, J. L. B. et al. (2017) ‘Accurate simulation of transcranial ultrasound propagation for ultrasonic neuromodulation and stimulation’, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 141(3), pp. 1726–1738. doi: 10.1121/1.4976339.

Rossi, S. et al. (2011) ‘Screening questionnaire before TMS: An update’, Clinical Neurophysiology, 122(8), p. 1686. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.12.037.

Rossi, S. et al. (2020) ‘Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines’, Clinical Neurophysiology. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.10.003.

Sanguinetti, J. L. et al. (2020) ‘Transcranial Focused Ultrasound to the Right Prefrontal Cortex Improves Mood and Alters Functional Connectivity in Humans’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00052.

Top, C. B., White, P. J. and McDannold, N. J. (2016) ‘Nonthermal ablation of deep brain targets: A simulation study on a large animal model’, Medical Physics, 43(2), pp. 870–882. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4939809.

Treeby, B. et al. (2018) ‘Equivalent-Source Acoustic Holography for Projecting Measured Ultrasound Fields Through Complex Media’, IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 65(10), pp. 1857–1864. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2018.2861895.

Treeby, B. E. et al. (2012) ‘Modeling nonlinear ultrasound propagation in heterogeneous media with power law absorption using a k-space pseudospectral method’, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 131(6), pp. 4324–4336. doi: 10.1121/1.4712021.

Treeby, B. E. and Cox, B. T. (2010) ‘Modeling power law absorption and dispersion for acoustic propagation using the fractional Laplacian’, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 127(5), pp. 2741–2748. doi: 10.1121/1.3377056.

Tyler, W. J., Lani, S. W. and Hwang, G. M. (2018) ‘Ultrasonic modulation of neural circuit activity’, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 50, pp. 222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.04.011.

Verhagen, L. et al. (2019) ‘Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates’, eLife. Edited by J. I. Gold et al., 8, p. e40541. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40541.

Wang, K. et al. (2012) ‘Modelling nonlinear ultrasound propagation in absorbing media using the k-Wave toolbox: experimental validation’, in 2012 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium. 2012 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, pp. 523–526. doi: 10.1109/ULTSYM.2012.0130.

Wu, S.-Y. et al. (2018) ‘Efficient Blood-Brain Barrier Opening in Primates with Neuronavigation-Guided Ultrasound and Real-Time Acoustic Mapping’, Scientific Reports, 8(1), p. 7978. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25904-9.

Yoo, S. et al. (2020) ‘Focused ultrasound excites neurons via mechanosensitive calcium accumulation and ion channel amplification’, bioRxiv, p. 2020.05.19.101196. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.19.101196.

8. License

Copyright (c) 2021, Donders Institute All rights reserved.

Unless otherwise separately undertaken by the Licensor, to the extent possible, the Licensor offers the Licensed Material as-is and as-available, and makes no representations or warranties of any kind concerning the Licensed Material, whether express, implied, statutory, or other. This includes, without limitation, warranties of title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, non-infringement, absence of latent or other defects, accuracy, or the presence or absence of errors, whether or not known or discoverable. Where disclaimers of warranties are not allowed in full or in part, this disclaimer may not apply to You. To the extent possible, in no event will the Licensor be liable to You on any legal theory (including, without limitation, negligence) or otherwise for any direct, special, indirect, incidental, consequential, punitive, exemplary, or other losses, costs, expenses, or damages arising out of this Public License or use of the Licensed Material, even if the Licensor has been advised of the possibility of such losses, costs, expenses, or damages. Where a limitation of liability is not allowed in full or in part, this limitation may not apply to You. The disclaimer of warranties and limitation of liability provided above shall be interpreted in a manner that, to the extent possible, most closely approximates an absolute disclaimer and waiver of all liability.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.